Chihuahua who took a tumble down the stairs

10 year old female spayed Chihuahua.

Presented after falling down 10-20 wood steps. Immediately afterward, she seemed unconscious for a few minutes, then became more alert but was unable to stand.

Laterally recumbent at presentation. Hypotherimc at 98.3 F. Dull but responsive. Tachycardic at 170 beats per minute. Left sided torticollis, non-ambulatory tetraparesis. No cranial nerve deficits were reported. Superficial and deep pain sensation were intact in all 4 limbs, and there was no obvious paraspinal pain or luxation.

In-house chemistry showed a hypoglobulinemia, mild hypokalemia, mild hyperglycemia and was otherwise within normal limits. In-house CBC was unremarkable.

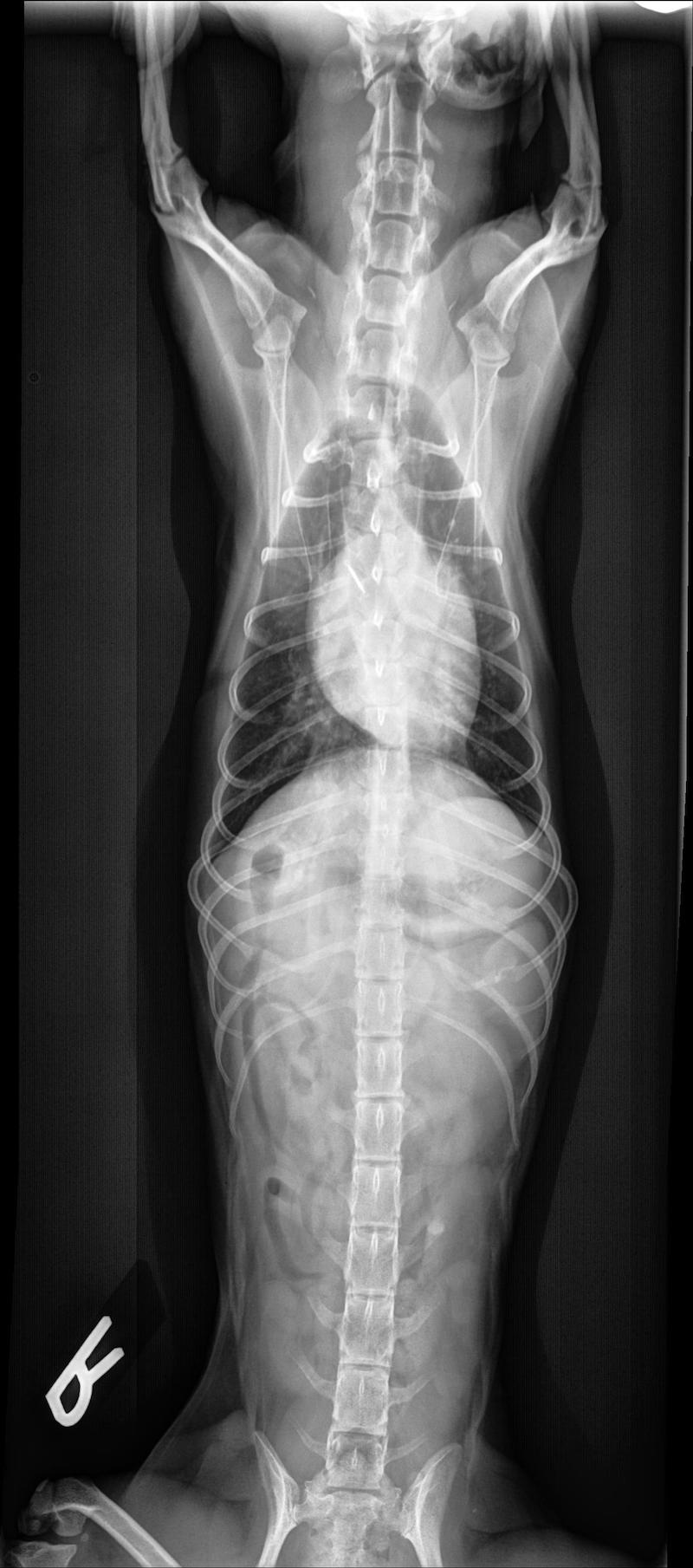

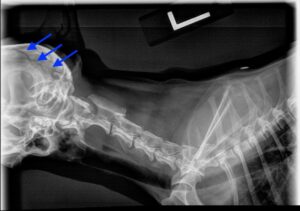

With concern for cervical spinal trauma, 3 view radiographs of the cervical spine (which included the thorax and the caudal aspect of the skull) were obtained.

Caudodorsal skull fracture, head trauma with evidence of secondary circulatory shock

Radiographic findings: The images showed a long fracture fissure running dorsal to much of the calavarium. The fracture fragment was minimally displaced in a dorsal direction. Mild narrowing of the C2-3 and T11-12 disk spaces were reported but thought to be incidental.

Case outcome: Following initial evaluation, Sofia was referred to a 24 hour emergency and critical care hospital for management of head trauma and shock. Prior to transfer, Sofia was given flow-by oxygen, heat support, IV crystalloids, and injections of midazolam and butorpanol.

Sofia spent about 48 hours in the ICU at the critical care hospital, where she was treated with continuous oxygen, fluid resuscitated and received CRI fentanyl for analgesia. Her vital signs and serial neurologic exams were monitored frequently. As her vascular status improved, she became bright and alert, began eating and was able to stand and walk, though sometimes circling or leaning to the left. Once transitioned to oral pain medications, she was discharged home with instructions for activity restriction and continued monitoring for neurologic decline. The minimally displaced calavarial fracture was expected to heal without complication. Unless a change in neurologic status was noted, there was no clear indication for advanced imaging or neurology consultation.

She followed up with her primary care veterinarian about a week later, at which time she was found to be ambulatory with a slight lean/list to the left and hind limb conscious proprioceptive delays. Her mentation and cranial nerve exam were normal, and she was comfortable on palpation of her head and neck.

Discussion: The most common physical exam finding for head trauma patients is altered mentation. While also common, findings such as cranial nerve and motor deficits may be absent at least initially. Once stabilized (evaluating and addressing airway, breathing, circulation), a thorough neurologic exam and diagnostics such as imaging can be performed. Plain radiography can usually identify skull and vertebral fractures. Advanced (cross sectional) imaging is needed to identify lesions such as subdural hemorrhage, which one study found to be present in 80% of dogs and cats with severe head injuries.

The pathophysiology of head trauma is divided into primary injury (occurring immediately on impact) and secondary injury (resulting from the metabolic cascade induced by primary injury). The magnitude of primary injury is determined by the degree of deformation of the brain tissue itself. The major cause of death in head trauma patients is the increase in intracranial pressure induced by the secondary metabolic changes that occur in the brain as a result of this deformation of brain (particularly cerebral cortex) tissue. Timely intervention to avoid hypoxemia (providing oxygen support), hypercarbia (promoting adequate ventilation), hypotension and hypovolemia (fluid support), ischemia (hypertonic saline, mannitol) can help to maintain cerebral perfusion in the face of increased intracranial pressure and help to limit the cycle of events that causes brain injury. Pain control and early nutritional support are also important components of head trauma treatment. Frequent serial neurologic exams, cardiorespiratory pattern monitoring, electrolyte and venous blood gas monitoring and arterial blood pressure monitoring are all important ongoing assessment tools.

The brain’s ability to compensate for injury and recover is very good. The majority of patients who survive the first 24 hours after a head injury can recover. However, the time it takes for meaningful recovery to occur is often prolonged, and the need for intensive nursing care during this period can limit survival to discharge from the hospital among veterinary head trauma patients. The dog in this case report was lucky to have experienced minimal secondary brain injury in spite of a dramatic looking skull fracture!