Coughing Cat

Corazon, a 9-year-old female spayed domestic short-haired indoor/outdoor cat, was presented to her veterinarian for a week-long history of progressive cough and labored breathing. She had one episode of retching and vomiting food the night prior to presentation. The owners reported no prior history of breathing concerns, cough or exercise intolerance.

Corazon was bright, alert, responsive. She was tachypneic with a mild inspiratory dyspnea. Heart sounds were noted to be muffled. Abdominal palpation was reported to be unremarkable.

I-stat and PCV/TS were unremarkable.

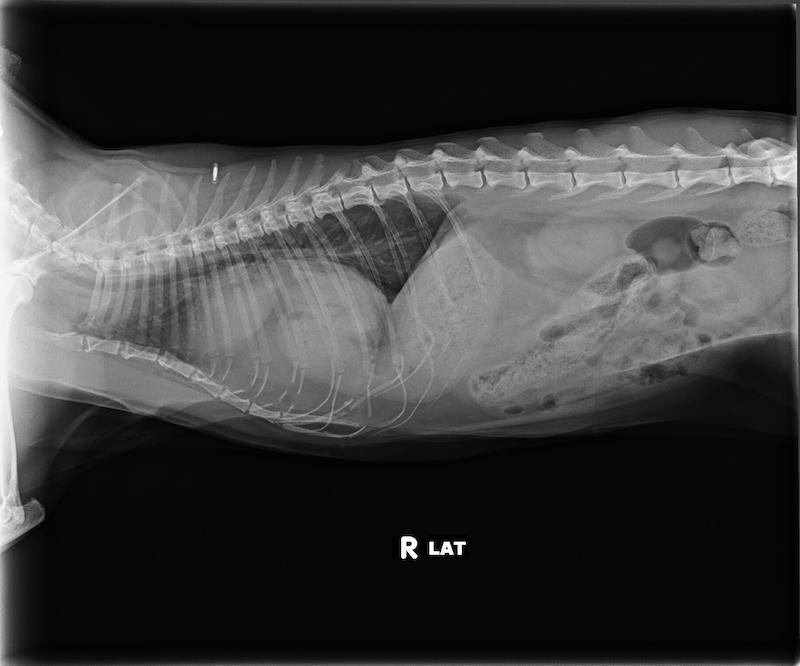

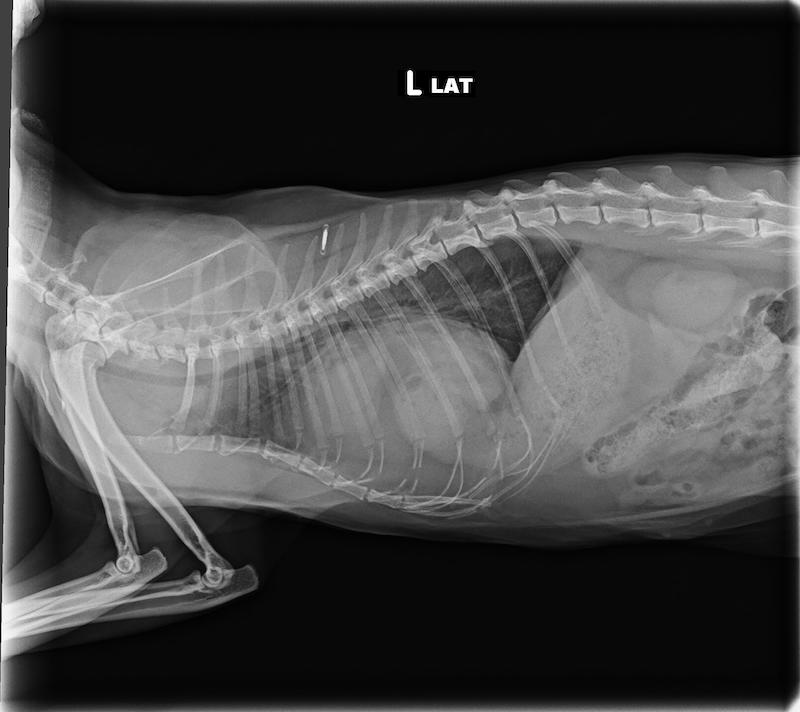

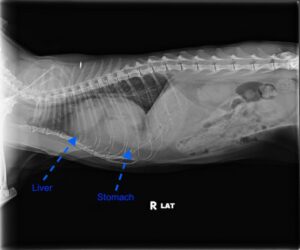

3-view thoracic radiographs were obtained. The cardiac silhouette was enlarged and globoid. The pylorus and the body of the stomach, as well as other soft tissue structures and fat, were overlying the cardiac silhouette. The cranioventral diaphragm was poorly delineated. The liver could not be identified within the abdomen. The trachea and caudal vena cava appeared normal. Other than a few subtle bronchial markings, the lung fields appeared normal. There was no pleural effusion noted.

Peritoneopericardial Diaphragmatic Hernia

Case outcome: Corazon was referred to a local specialty hospital for surgery. She recovered uneventfully and was discharged from the hospital, purring, 2 days later. The owners reported that she continued to enjoy napping in the sun and meowing loudly in the middle of the night.

Discussion: Peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia is a congenital condition that occurs during embryonic development. Unlike a traumatic diaphragmatic hernia, this is never an acquired condition (i.e., it does not result from trauma to the patient). It occurs due to a genetic anomaly, toxin/teratogen exposure in the dam, illness of the dam or as a result of trauma to the embryonic structure (septum transversum) that normally goes on to form the ventral diaphragm. When the septum transversum fails to fold normally, the result is a communication between the peritoneal cavity and the pericardium.

Clinical signs occur when abdominal organs herniate into the pericardial sac. Herniation of the liver is most common. Gallbladder, small intestines, omentum, stomach, and spleen can also herniate. If herniated organs become strangulated, dysfunction of those organ systems, as well as shock can occur. Space-occupying herniation of organs into the pericardium and development of pericardial effusion can also cause cardiac tamponade, which can lead to right-sided heart failure and subsequent respiratory compromise. Patients with PPDH usually present with respiratory signs or non-specific signs such as fever, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, or lethargy.

Plain thoracic radiography is usually sufficient for definitive diagnosis. Contrast studies can be performed for definitive diagnosis if GI structures are present within the pericardium. Ultrasound can be used for the visualization of abdominal organs within the pericardium or an irregularity in the diaphragm. CT or MRI can also make the diagnosis but are generally unnecessary.

The recommended treatment for PPDH is surgery. Complications can include re-expansion pulmonary edema, pneumopericardium, and constrictive pericarditis. If there are no complications, clinical signs typically resolve following surgical correction and prognosis is excellent. In patients that are poor surgical candidates, have mild clinical signs, or whose owners elect not to pursue surgery, symptomatic medical management may be warranted, however, these patients remain at risk for complications that can progress acutely.